Steven A. S l y t e r

FORENSIC DOCUMENT EXAMINATION

114 Palermo Place, Lady Lake, Florida 32159

502-479-9200

More than fifty years of experience as a Forensic Document Examiner

Overview

• Semi-retired now after more than fifty years experience in full-time, private practice

Earned certifications through accredited/validated written examinations

- Served as officer in professional organizations

• Fifty plus years of full time experience in State and Federal courts

- Civil cases - working with both plaintiff and defense counsel

- Criminal cases - working with both prosecution and defense

counsel

• Author/Editor

• Lecturer

Recognized as an expert in the areas of signature authenticity; forgery identification; disguised writings; indented writings; typewriter identification; anonymous letters; graffiti, age of documents and/or writings; alterations to documents and obliterated writings.

Publications

Books

Forensic Signature Examination

by Steven A. Slyter,

Charles C. Thomas Publishing, Springfield, IL. 1995.

This book details the author’s approach to a step-by-step method

for conducting an analysis of signatures. This process produces data

for every element of the analysis. Data leads to an objective statement

of the forensic value of the evidence and the level of certainty that

evidence supports. This work is the product of decades of effort to

reduce the subjectivity in signature and handwriting examination.

The Effects of Alterations to

Documents,

by Steven A. Slyter,

Am Jur Proof of Facts,

Volume 29, Third Series.

Lawyers Cooperative Publishing, Rochester, NY. 1995.

This section was written in the early 1990‘s at the request of

the publisher. Semi-retired now I am selective in accepting

assignments that require taking equipment out to conduct

the examination of original documents. I am available to

consult on such cases or to review work done by other

examiners.

Articles

A Simplified L. I. D. Design (AFDE Volume V, Fall 1992),

Copy Photography for Document Examiners (AFDE Volume II, Fall 1988),

AFDE’s Apprenticeship Program (AFDE Volume V, Fall 1992),

These three are articles by Steven A. Slyter were published in The Journal of Forensic Document Examination, Association of Forensic Document Examiners. (This Journal is available on West Law.)

Looking Beyond the Visible

by Steven A. Slyter published by Studio Photography Magazine. (July 1988)

Working with Questioned Document Examiners

by Steven A. Slyter published by Studio Photography Magazine. August 1987)

For three and one-half years (in the early 1990’s) I was Technical Editor of The Journal of Forensic Document Examination. I participated in the review and editing of the articles published at that time.

Cases in the News . . .

The Discovery Channel

2001 Season

“The Invisible Killers”

The story of a fabricated suicide note.

_______________________________

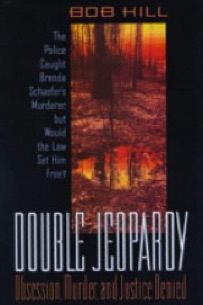

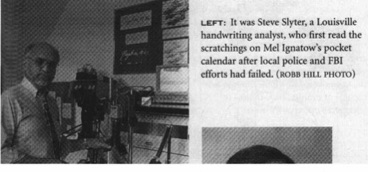

Double Jeopardy

By Bob Hill, Published by Morrow (1995)

Read about S. A. Slyter’s success in finding crucial

evidence missed by the F.B.I. lab.

Frequently Asked Questions

By far the most common question is...

‘What is this going to cost?’

I am semi-retired and limiting my case load to 2 or 3 cases per month with the understanding that if testimony is needed I prefer to testify in a video deposition.

I am accepting signature or handwriting cases. I am selective in accepting altered document cases that will require dragging equipment out to examine original documents.

My retainer is $1000 for the analysis, with a verbal report. This retainer in non-refundable. A detailed written report including exhibts is an additional $2000 fee. Deposition testimony will be presented here in Florida. That fee is $1500 plus time needed for preparation billed at $250 per hour.

When the validity of a signature is in question, how does an expert proceed?

Forensic signature examination has always been a subjective process. For decades I have worked to make this process more objective. To the best of my knowledge I am the only examiner working in a data driven methodology. This methodology allows assessment of the forensic value of the evidence and an objective estimate of the level of certainty the evidence will support. It is my opinion that far too often document examiners greatly overstate the level of certainty they assign to their opinion. (For a thorough discussion of this topic see Steven A. Slyter’s book Forensic Signature Examination, Charles Thomas Publishing, Springfield, IL.)

What are the most common reasons for hiring a document expert?

Document experts are hired to assist attorneys, clients and courts when specialized knowledge is needed to better understand how an evidentiary document came to exist in the form presented.

There may be questions raised as to the validity of one or more signatures; the authorship of writings; the physical facts of the document’s creation (i.e. printing, typewriting, copier used, pens used, etc.) or, the existence of and/or nature of alterations to the document. Anything that may have affected the way the subject document was originally produced and what has happened to it since, might become the focus of the document expert’s examination. By far, the most frequent question a document expert addresses involves the validity of a key signature.

Routine business relies heavily on the use of signatures as proof of consent or confirmation of commitments. From wills and checks to contracts and issuing of orders, we accept signatures as proof that the person understood and approved the content of the document. From the millions of documents signed each day there will be a small percentage of instances where signatures are forged. In a smaller number of cases, genuine signatures are later denied.

When disputed or suspect signatures are brought to an expert for examination, the process actually begins with putting the questioned signature aside to collect and examine genuine signatures of the person whose name is involved (referred to as known or exemplar signatures). It is necessary to study a collection of genuine signatures to develop a fair and reasonable definition of the subject’s signature habits. Most of us have two or three different styles of signature. For example, we frequently sign a routine receipt for gasoline with a style of signature far less formal than we would use to sign our will or a deed. This collective definition of normal variations will form the yardstick against which the questioned signature will be compared.

How many known signatures will be needed?

The purpose of the known signatures is to define the subject’s range of normal signature variations so that the signature in question can be tested against that definition. The number of known signatures needed depends on how much the writer’s natural signatures vary. The best standards are those drawn from the writer’s normal-course-of-business — signatures produced without any thought or expectation they would later be used as standards for comparison.

An ideal situation offers a collection of signatures large enough that the expert can draw from that pool until no further variations can be found. More practically, if the examination shows little variation in the first several signatures examined the expert might well be satisfied with a fairly small collection. When a few exemplars sufficiently define the writer’s range of variation so as to encompass the writing habits seen in the signature in question then obviously, there is no need to search for more exemplars.

If the variations are great in the first standards examined, it will be necessary to gather a larger collection. For most writers, 12 to 20 signatures will allow the development of an accurate and reliable definition of routine signature habits.

What are some possible sources for normal-course-of-business signatures?

The hope is to assemble a collection of signatures drawn from reliable sources that will accurately define the writer’s routine signature habits. Signatures from documents of similar importance to the questioned document are most useful. Signatures timely to the date of the Subject document are valuable.

As mentioned above, some documents are frequently signed in a careless way, others may be signed with more attention to what we are doing. Sources of known signatures might include: personal papers, such as canceled checks, personal business records, tax forms, letters and notes to friends and family; personal journals; recipes, and entries in a family Bible. Public record sources that can be checked include deeds and mortgages, licenses (marriage license, driver’s license, hunting or fishing licenses), voter registration cards and poll records, as well as many court records.

If an adequate collection of normal-course-of-business exemplars cannot be found, the expert must turn to “request standards.” Request standards are witnessed signatures and writings produced specifically for the expert’s use. Getting an accurate writing sample is more difficult than it might seem. Understandably self-consciousness can make it hard to get free flowing, common signatures from a person focused on the act of signing. Of course, the possibility of intentional disguise of the standards must be taken into consideration.

What if original documents are not available? Can an expert work from copies?

It is always preferable to work with original documents, however some situations make it impossible to do so. In many cases reliable work can be done with modern machine scans or copies. But opinions reached from copies cannot be expressed with the same level of certainty as those reached through an examination of the originals.

An examination of copies can not be as thorough as an examination of originals. Often an examination is started with high quality copies and the originals are examined later.

Working with originals the expert can say with confidence that:

a) the original does exist (with computer scanners and copy machines in wide use, it is becoming more common for the expert to encounter copies of documents that never actually existed — this possibility must be born in mind when working with copies) and,

b) every element or feature of the signature that can be examined, has been examined.

Obviously, work done only with copies negates both of these advantages.

What can be done to investigate the possibility a document has been altered?

Next to questions involving signatures or handwriting, experts are most often asked to look into questions involving possible alterations to documents. The document expert has an array of tests and tools for examining alterations.

Every physical detail of the document might require testing. Papers, inks, typewriters/printers, indentations, printing — any detail —might need to be tested. Of course, testing for alterations requires examination of the original documents.

For a thorough discussion of this topic see Steven A. Slyter’s chapter in Am Jur Proof of Facts, Vol. 29, 3rd Series. The Effects of Alterations to Documents.

As mentioned, I am available to consult on alteration issues but selective in accepting these assignments.

When needed — how does one select a document expert?

There is no degree nor license for document experts. The range of skills mastered by practitioners varies greatly. Not all who claim to be document examiners or handwriting experts, do in fact possess the skills and knowledge necessary to this work.

Unfortunately, certifications mean very little. There are numerous organizations offering certification. Some require nothing more than completing an in-house, open book examination, others require meeting more stringent demands and demonstration of one’s skills. Experience is far more important than cetifications.

Attorneys are apt to have the most up-to-date information about experts in your area. Seek recommendations from attorneys, judges, and police officers. Contact any expert you are considering hiring and ask for a list of references. That list should include attorneys the expert has worked with AND the names of some attorneys who have cross-examined the expert. If possible, seek out and review copies of the expert’s depositions.

Ask about court experience — how frequently has the examiner testified, in which courts, in what types of cases? Ask your attorney to inquire about or read some of the expert’s testimony. In making your selection you must be comfortable that the expert you select will be capable, thorough, objective and honest throughout the course of the case.

Ask a question

I am always available and willing to try to answer questions about forensic document examination. If you have a question that has not been addressed above, please feel free to contact me and I will be glad to explore the question with you.

Please contact me by phone at -- 502-479-9200

Or, by email at -- steven@stevenaslyter.com